Get More Articles Like This One

It is held today that America has entered a “post-Christian culture.” Theologically orthodox Christians are told that their vision of life and doctrine—a vision widely affirmed over two thousand years of Western history—no longer will be undergirded and promulgated by the increasingly secular social structures and cultural forces in our nation. Therefore, the argument goes, Western Christians must find new ways to live out their faith as exiles or outsiders.

In the past year, two books were released that claim to offer wisdom for believers struggling to navigate this new terrain. Both attempt to retrieve, and then to adapt creatively, examples from church history that provide paradigms for Christians to emulate.

In The Benedict Option, Rod Dreher proposes Saint Benedict and his monastic communities of the Early Middle Ages. Dreher sees the West’s current state of decline as the logical outworking of its secular Enlightenment foundations. In response, he urges Christians to give up their attempt to redeem all of American culture through direct political and social action. Instead, they must move willingly to the margins of society and live out a countercultural existence by embodying Benedict’s values such as prayer, work, education, hospitality and so forth.

In The Pietist Option, Christopher Gehrz and Mark Pattie III propose Philip Spener and other seventeenth-century German Pietists to be worthy of consideration. In contrast to Dreher, these authors aver that the church ought to adopt the posture of being “a servant of the culture” through subjective spiritual formation combined with an explicit commitment to Progressive political activism.

It is not my intent in this article to offer a review of either book. I do believe they are worth reading and contain some helpful observations and practical suggestions for Christian disciples who desire to be faithful in the midst of confusing times. However, I also have many critical concerns, not the least of which is their tacit assumption that the decline of Western Christendom (and indeed, of Western culture more broadly) is inevitable, a done deal. Neither of them seems interested in asking the deeper intellectual questions: What is the basic foundation that supports Western culture, or any culture for that matter? And what was the cause of previous revivals of culture in world history?

Thinkers as different as Ayn Rand, Richard Weaver, and Francis Schaeffer all made the profoundly true observation that culture is determined most fundamentally by philosophical ideas, and that cultural history progresses or declines based on the predominant philosophical ideas in any given society. Therefore, to understand why Western culture is declining, we must ask ourselves what philosophical ideas are dominant in our universities, political institutions, and professional media. Then, to reverse this trend, we must ask what ideas have been shown in history to spark genuine renewal and vitality?

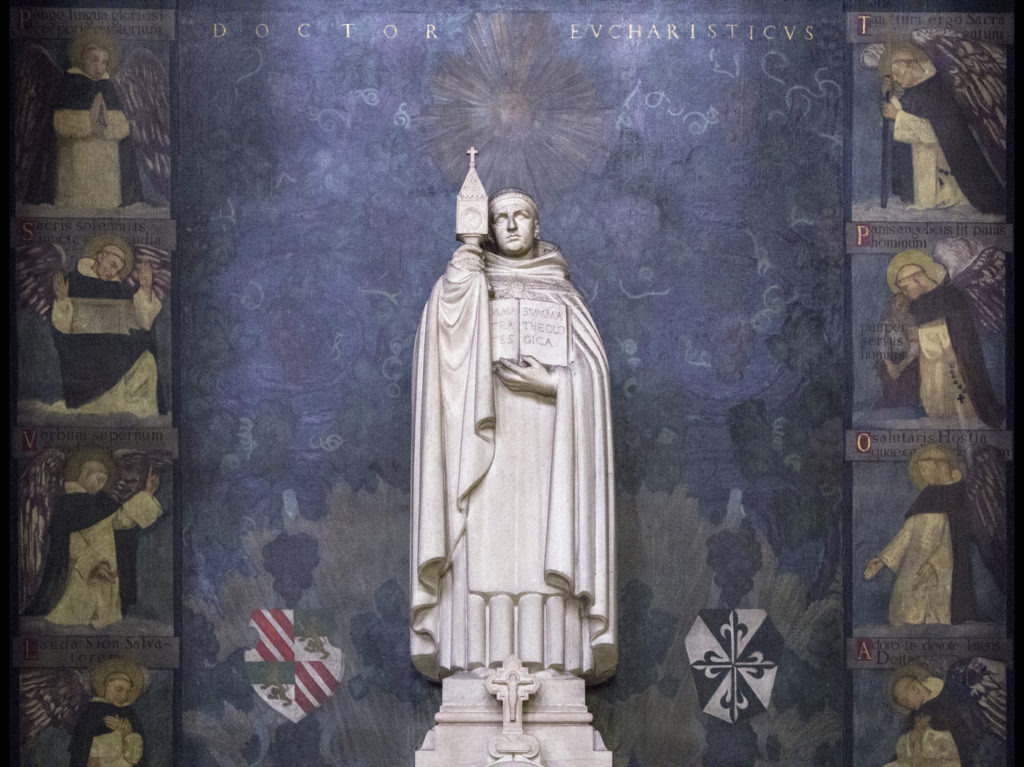

In an effort to contribute an answer to that second question, I offer here a third “option” for Christians attempting to discern their strategy for this “post-Christian” world. I call it the Aquinas Option.

It was Ayn Rand (in the title essay of her book For the New Intellectual, and elsewhere) who credited St. Thomas Aquinas with laying the philosophical foundation of the European Renaissance. Aquinas’ transmission of Aristotelian reason into the medieval mind, Rand taught, paved the way for the flowering of European culture: the recovery of learning, the resurgence of commerce and trade, and the awakening of the arts and sciences. In that climate, it was only a matter of time before the unified dominance of the Christian church was fragmented, forcing it to address needed reforms and remembering its primary call to preach, evangelize, and engage in practical acts of service in the world. This was not a loss for Christianity—it was a winning reminder of its true identity as the herald or witness, not the master.

How did Aquinas provide the intellectual fuel that led ultimately to such world-changing events? Let me offer three brief observations.

First, Aquinas affirmed the Aristotelian commitment to understand reality objectively through the use of observation and reason. The goal of knowledge is not to understand my subjective experiences and then adapt reality to suit them. Rather, it is to perceive reality as it is, utilizing my mind to discern its nature and then acting in accord with its nature. The first step in cultural revitalization is to fight for an unwavering commitment to the premise that objective knowledge is achievable to the individual through reason. As John Wenrich (the newly-elected president of my denomination) frequently says, “There is no vitality without reality.”

Second, Aquinas carried on a precedent set by early Christian thinkers such as Justin Martyr, Clement of Alexandria, and Augustine: He affirmed that “all truth is God’s truth,” and therefore he entered conversation with people of other faiths and even with outright pagans. His magnum opus, the Summa Theologiae, is notable for its frequent references to Scripture, but it also includes substantial quotations from Aristotle (who Aquinas dubbed “the Philosopher”), Jewish rabbi/philosopher Moses Maimonides, and Muslim theologians Avicenna and Averroës.

In citing these and other interlocutors, Aquinas always avoided setting up a straw man to demolish. On the contrary, he studiously presented the best possible version of another thinker’s arguments—sometimes better than the other thinker presented it! Thus demonstrating a dispassionate understanding of a differing point of view, only then did he respond with his own understanding of the truth. If Aquinas had lived in the era of social media and the twenty-four hour news cycle, I think he would have eschewed dismissive generalizations and simplistic talking points in favor of rigorous but respectful debate in the manner of Dave Rubin, Ben Shapiro, Jordan Peterson, and Yaron Brook.

Finally, Aquinas reintroduced into medieval society the ethical principle that the individual’s “fulfillment” or “happiness” ought to be the goal of ethical behavior. Prior to the Aristotelian revival in the high middle ages, ethics often was reduced to little more than “confessing your sins” and avoiding such sins—specifically the seven deadly sins of pride, envy, anger, sloth, avarice, gluttony, and lust. Morality became focused on the evil to be avoided, rather than the good to be pursued.

In contrast, Aquinas held that individual happiness is a good to be pursued in the moral life. He gave humans an internal motive based on personal joy and hope, rather than on guilt. This positive motive power reaffirmed the Christian tenet that each person—despite sin—is created in the Image of God, unleashing the individual to acquire moral virtues and to act with confidence in his or her own worth and efficacy. In today’s toxic culture, when guilt and shame are being utilized to immobilize or silence one’s opponents, we need a positive moral project: one that encourages each individual to develop life-affirming goals and to pursue them with the ultimate end of receiving eternal happiness.

In these three observations, I see Aquinas providing us with the true option for cultural revival. They are not merely pragmatic tactics or subversive strategies. They are deeper and more profoundly spiritual, because they are rooted in the basic ideas upon on which a healthy and vital culture depends. In his fundamental approach to knowledge—objective reality, respectful debate about ideas, and an ethic of personal fulfillment—St. Thomas Aquinas has given Christians intellectual tools necessary to revitalize our culture.

Jeffrey Kahl

Jeff holds a B.A. degree in history and political science from Ashland University and an M.Div. from Ashland Theological Seminary. He’s a full time pastor and part time scholar. Like C. S. Lewis, he considers himself “a converted pagan living among apostate puritans.”